The Deep-mapping Sanctuaries project is currently focused on the healing sanctuary of Asklepios in Pergamon, a shrine with a biography that extends across 600 years and more, encompassing thousands of generations of encounters and interactions and their narratives. Access to these narratives, however, is now only available through specialist reports and secondary publications. This project aims to integrate this data in a comprehensive deep map, allowing for both individual accounts and larger patterns to emerge.

Sanctuaries in the ancient world were at the crossroads of diverse urban narratives. Social, economic, and (geo)political motives were intertwined with religious aspirations, creating a vibrant space of overlapping and sometimes contesting voices that channeled the dynamics of urban flows. The sanctuary of Asklepios near Pergamon was such a space. Developing from a natural shrine in a spring-fed basin to a place of healing, the Asklepieion gradually became a center of gravity, drawing travellers near and far, and attracting the attention of Hellenistic kings, the local elite, Roman emperors, as well as those seeking healing. By the imperial period, Asklepios had become Pergameus Deus, the principal god of the city.

Legendary beginnings

According to Pausanias (2.26.8-9 ), the cult of Asklepios was founded by a certain Archias, who injured himself while hunting in the mountains near Pergamon and went to Epidauros where he was healed. He subsequently brought the cult back to the area with him, presumably in the 4th c BC. A 2nd c BC inscription mentions an Archias as father of Asklepiades, whose descendants fulfilled the priesthood ( IvP II 251 ). Another Archias from Pergamon is mentioned in an early 2nd c BC inscription from Epidauros – this Archias was envoy (theorodokos) during the rule of Eumenes I ( IG IV² 1 60 ). In any event, these were a few of the prominent figures that played a role in promoting the cult and developing the sanctuary into a prominent sacred center.

Site biography – ‘five easy phases’

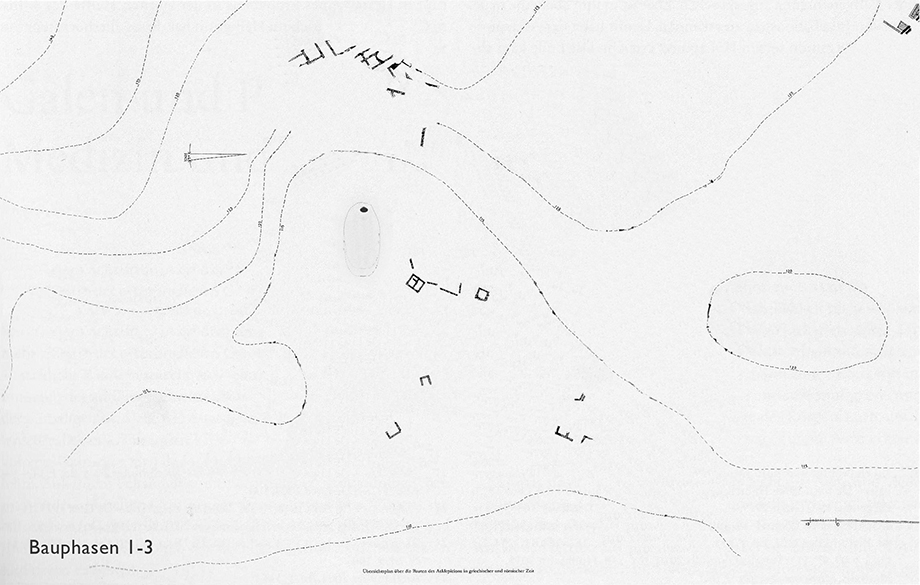

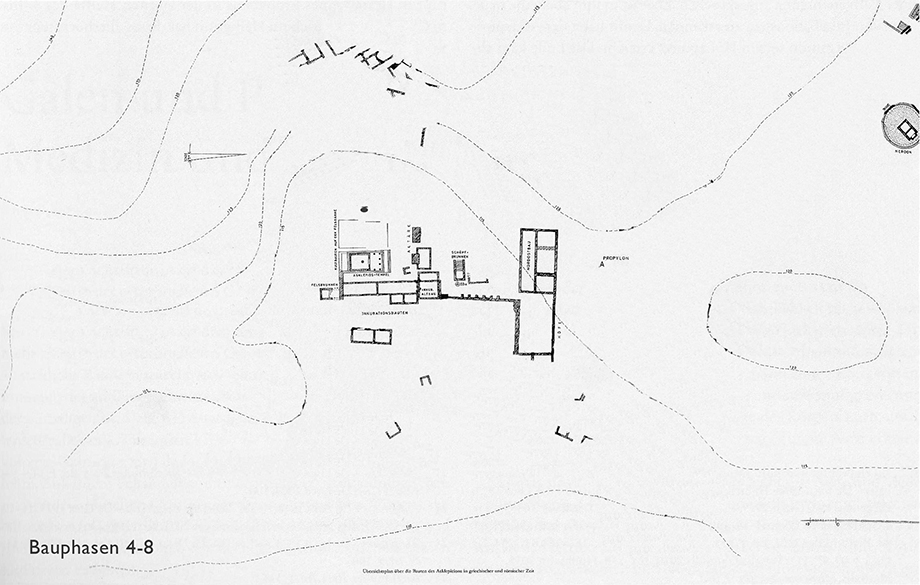

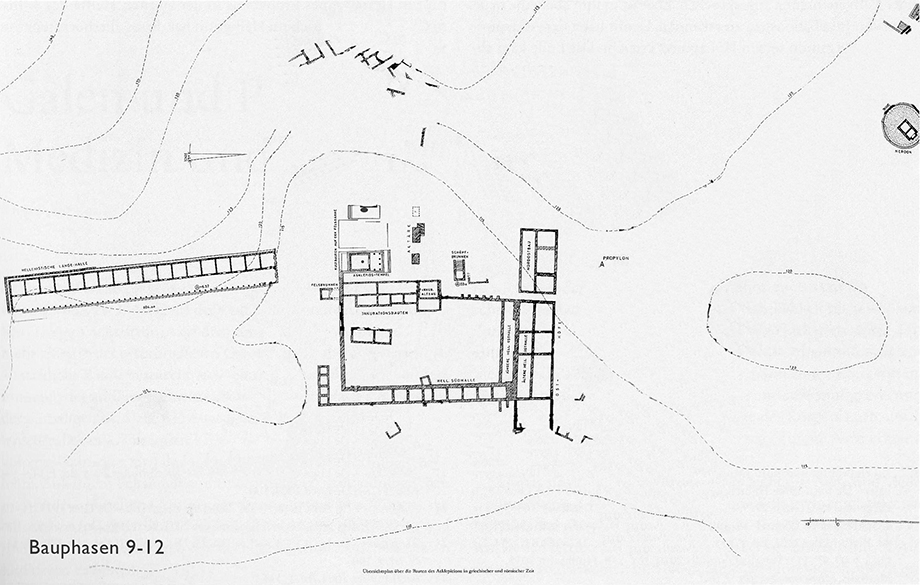

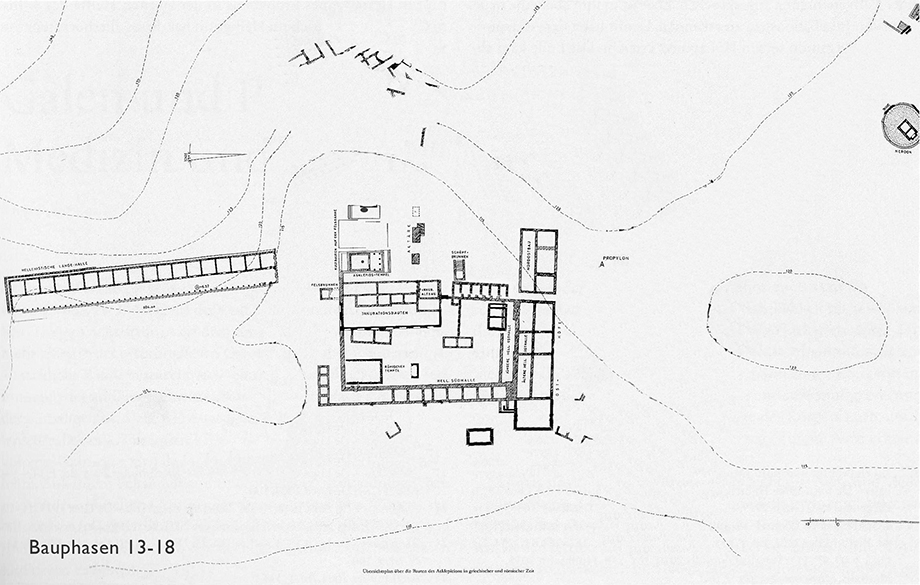

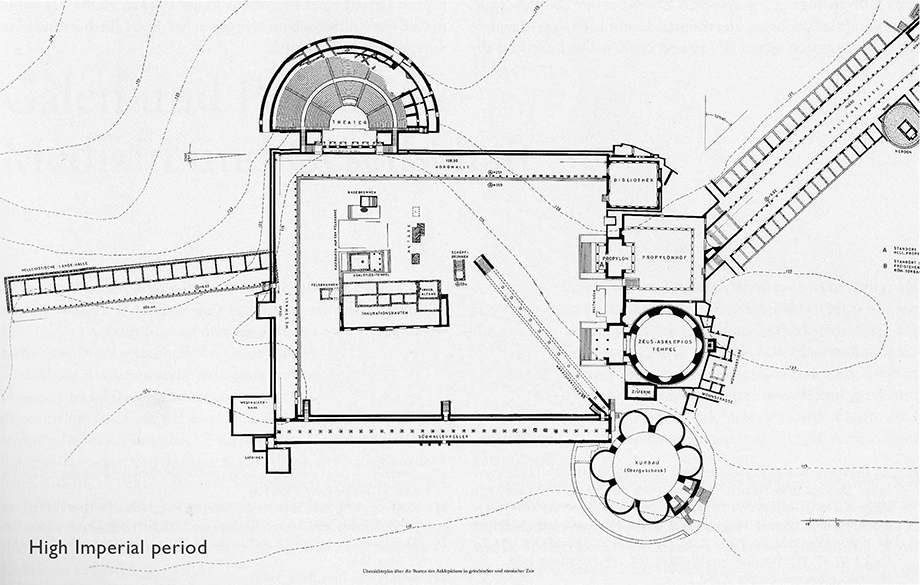

The excavators identified 18 different Bauphasen (construction phases) of the shrine, published in the first volume of the excavation reports (AvP XI). Luckily they also clustered these into five main phases, making it easier to follow the development of the shrine. The imperial phase of the shrine is best known, but one of the aims of this project is to tease out the pre-imperial phases, i.e. the development of the sanctuary in the Hellenistic and early Roman era. Overshadowed by the exceptional architecture of the imperial period, these phases deserve more attention, in order to understand the human interaction and progression of the sanctuary into a major supraregional shrine, especially under the Attalid kings.

The images below are based on Taf. 84 in AvP XI.1, in which the five major phases of development are identified.

This last major phase of the sanctuary regularly features in the Sacred Tales (Hieroi Logoi) of Aelius Aristides.

Literary sources – Aelius Aristides

The Asklepieion appears in a number of ancient accounts (see ToposText ) , including Polybios (32.15.3-4), Appian (Mithridatic Wars 4.23, 9.60), Pausanias (Travels in Greece 3.26.10, 5.13.3), Lucian (The Sky-Man 24), the Suda (2914), Tacitus (Annals 3.63), Philostratos (Life of Apollonios of Tyana), and Herodian (History of the Empire), but none are as extensive as the references in Aelius Aristides’ Hieroi Logoi (Sacred Tales). In this work, the chronically ill orator recorded his dreams, encounters, and experiences during his stay at the Asklepieion of Pergamon in the 2nd AD. The Hieroi Logoi provide a rare insider’s view of the healing as well as religious experience through the shrine and its monuments, its rituals, and the people that interacted there. As Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis observed, “…incubants saw each other and themselves moving as a group amongst the statues of the gods and amongst visual narratives—sculptural and inscriptional—of past pilgrims who had been favoured by the god. …In this sense they became part of a timeless miraculous community through the re-enactment of ritual and spatial choreography.” (Petsalis-Diomides 2010, 237).

Because of the rich data, the Hieroi Logoi served as a prototype of a deep map, created with the assistance of the Geodienst in 2020, and Alexandra Katevaini. See the story map Aelius Aristides and the Asklepieion of Pergamon (work-in-progress!)

Data sources in the Asklepieion

Literary texts are only one of the sources that give insights into human interaction and the spatial situation of the Asklepieion. Inscriptions are another important source. At the Asklepieion, there is a wide range that includes dedications which can take a wide range of forms, from small individual private offerings out of gratitude for healing (many on tabula ansata), small altars, or entire monumental structures (as inscribed on their architraves). Dedications also indicate the presence of other divinities, such as Apollo, Hygieia, Telesphoros, and Artemis, but also the rulers. Honorific decrees for the elite are also prevalent, showing the sanctuary as a podium for the (mostly local) elite to be put on display. Coins are another important source, as another indicator of the network or ‘catchment area’ of the sanctuary, based on their origin, but also for iconography: Pergamene coinage from the imperial period shows how Asklepios as Pergameus Deus, the principal god. Coin hoards also point to times of crisis. An important material category includes ceramics, which may indicate rituals and their locations, as well as everyday practices in the sanctuary. Terracottas also give an idea as to votive and dedicatory practices, as well as localized religious imaginaries. Sculpture is well represented at the sanctuary, and particularly along the sacred way, which held numerous references to classical and philosophical figures, as well as rulers – this area also intersected with the funerary zone of Pergamon. Finally, the monumental architecture of the sanctuary, as briefly sketched above, informs us as to how this unique space was shaped and how rituals were shaped – implicit in this are the constantly shifting earthworks, the engineering and impact on the local hydrologies in this spring-fed basin.

Each of these data types has a story to tell, but it is especially the combination of these in place that can show patterns of collective and individual behavior, and inform on individual decisions against this expansive religious, social, economic, and political context. An issue is that the sources are largely published in specialist reports, typically accessible to experts in the discipline. A central aim of this deep-mapping project is to bring the different data sources together, integrating it into a comprehenisive, albeit complex, Geographic Information System (GIS) that can help releaase some of the stories now tucked away in these reports.

Alexandra Katevaini wrote a story map on how we are incorporating the different kinds of data in a Deep Map of the Asklepieion.

Fieldwork – 2019-current

Recent fieldwork in Pergamon includes the surroundings of the shrine in order to better understand its economic and social embedding in the landscape of Pergamon, and its relationship with the city. Ulrich Mania directed field surveys in the 2019-2020 around the Asklepieion with this purpose in mind (Mania 2021). This survey is embedded in the project The Transformation of the Pergamon Microregion, directed by Felix Pirson, Güler Ateş and Ulrich Mania of the DAI Istanbul. See also Pirson, F. et al. (2021). Pergamon – Das neue Forschungsprogramm und die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2019. Archäologischer Anzeiger, 2020/2, 1-245; also the DAI TransPergMikro blogspace:

https://www.dainst.blog/transpergmikro .

For more information, visit the story map…

References

Archaeological reports

Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion

- Ziegenhaus, O. and G. de Luca (1968) Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion. Teil 1. Der südliche Temenosbezirk in hellenistischer und frührömische, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Ziegenhaus, O. (1975) Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion. Teil 2. Der nördliche Temenosbezirk und angrenzende Anlagen in hellenistischer und frührömischer Zeit, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Ziegenhaus, O. (1981) Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion. Teil 3. Die Kultbauten aus römischer Zeit an der Ostseite des Heiligen Bezirks, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- De Luca, G. (1984) Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion. Teil 4. Via Tecta und Hallenstraße. Die Funde, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Hoffmann, A. and G. De Luca (2011) Altertümer von Pergamon XI. Das Asklepieion. Teil 5. Die Platzhallen und die zugehörigen Annexbauten in römischer Zeit, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Regular reports

- Wiegand, T. and W. Weber (1932) Zweiter Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Pergamon 1928-32: das Asklepieion, Abhandlungen der preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, 0233-2779. Jg. 1932, Nr. 5, Berlin: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Mania, U. (2021) ‘Der Survey im Umfeld des Asklepieions ‘, in Pirson, F., M. Aksan, P. Bes and F. Becker (2021) ‘Pergamon – Das neue Forschungsprogramm und die Arbeiten in der Kampagne 2019’, Archäologischer Anzeiger 2020/2, 1-245, pp. 188-196.

Epigraphy

- IvP III = Habicht, C. (1969) Altertümer von Pergamon VIII. Die Inschriften von Pergamon. Teil 3. Die Inschriften des Asklepieions, Altertümer von Pergamon, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Meier, L. (2009) ‘Inschriften aus dem Asklepieion von Pergamon’, Chiron 39, 395-408.

- Müller, H. (1987) ‘Ein Heilungsbericht aus dem Asklepieion’, Chiron 17, 193-233.

- Robert, L. (1984) ‘Un décret de Pergame’, BCH 108, 481.

Thematic studies

A lot has been written on the Asklepieion – this represents a selection of works referenced in this project.

On architecture

- Deubner, O. (1938) Das Asklepieion von Pergamon; kurze vorläufige Beschreibung, Berlin: Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft.

- Jones, C.P. (1998) ‘Aelius Aristides and the Asklepieion’, in: H. Koester ed. Pergamon citadel of the gods. Archaeological record, literary description, and religious development, Harvard Theological Studies 46, Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 63-77.

- Melfi, M. (2016) ‘The archaeology of the Asclepieum of Pergamon’, in: D.A. Russell, M. Trapp and H.-G. Nesselrath eds, In praise of Asclepius. Aelius Aristides, selected prose hymns, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 89-114.

- Riethmüller, J.W. (2011) ‘Das Asklepieion von Pergamon’, in: R. Grüßinger, V. Kästner, A. Scholl, I. Geske and J. Laurentius eds, Pergamon. Panorama der antiken Metropole. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung, Petersberg, Berlin: Imhof, 228-234.

- Strocka, V.M. (2012) ‘Bauphasen des kaiserzeitlichen Asklepieions von Pergamon’, Istanbuler Mitteilungen 62, 199-287.

On inscriptions

- Ferretti, L. (2022) ‘Cohabitations de dédicaces dans l’ Asclépiéion de Pergame. Divinités – Textes – Supports’, in: B. Amiri ed. Lieux de culte, lieux de cohabitation dans le monde romain, Besançon: Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, 165-184.

- Ferretti, L. (2022) ‘Visual and Spatial Dynamics of Written Texts: Dedications in the Asclepieion of Pergamon’, Istanbuler Mitteilungen 71, in press.Hoffmann, A. (1998) ‘The Roman remodeling of the Asklepieion’, in: H. Koester ed. Pergamon citadel of the gods. Archaeological record, literary description, and religious development, Harvard Theological Studies 46, Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 41-61.

- Mathys, M. (2014) Architekturstiftungen und Ehrenstatuen. Untersuchungen zur visuellen Repräsentation der Oberschicht im späthellenistischen und kaiserzeitlichen Pergamon, Darmstadt.

- Sokolowski, F. (1973) ‘On the new Pergamene Lex sacra’, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies XIV, 407-413.

On religious / political aspects

- Caneva, S. (2019) ‘Variations dans le paysage sacré de Pergame. L’Asklépieion et le temple de la terrasse du théâtre’, Kernos, 151–190.

- Halfmann, H. (2004) ‘Pergamener im römischen Senat’, IstMitt, 519-528.

- Kranz, P. (2004) Pergameus Deus. Archäologische und numismatische Studien zu den Darstellungen des Asklepios in Pergamon während Hellenismus und Kaiserzeit ; mit einem Exkurs zur Überlieferung statuarischer Bildwerke in der Antike, Mönnesee: Bibliopolis.

- Ohlemutz, E. (1940) Die Kulte und Heiligtümer der Götter in Pergamon, Würzburg: Giessen.Schalles, H.-J. (1985) Untersuchungen zur Kulturpolitik der pergamenischen Herrscher im dritten Jahrhundert vor Christus, Istanbuler Forschungen 36, Tübingen: Wasmuth.

- Tozan, M. (in press) ‘The Asklepieion of Pergamon as a sacred landscape of wellness to the Graeco-Roman elite’, in: C.G. Williamson ed. Sacred landscapes, connecting routes. Religious topographies in the Graeco-Roman world, Caeculus, Leuven: Peeters.

On healing and Aelius Aristides

- Brabant, D. (2006) ‘Persönliche Gotteserfahrung und religiöse Gruppe. Die Therapeutai des Asklepios in Pergamon’, in: A. Gutsfeld and D.-A. Koch eds, Vereine, Synagogen und Gemeinden im kaiserzeitlichen Kleinasien. Actes d’un colloque intitulé « Collegia, sunagogai, ekklesiai/Vereine, Synagogen, Gemeinden » tenu à Münster en 2001, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 61-75.

- Jones, C.P. (1998) ‘Aelius Aristides and the Asklepieion’, in: H. Koester ed. Pergamon citadel of the gods. Archaeological record, literary description, and religious development, Harvard Theological Studies 46, Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 63-77.

- Petridou, G. (2017) ‘Contesting religious and medical expertise. The therapeutai of Pergamum as religious and medical entrepreneurs’, in: R.L. Gordon, G. Petridou and J. Rüpke eds, Beyond Priesthood. Religious entrepreneurs and innovators in the Roman Empire, Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten 66, Berlin: De Gruyter, 185-214.

- Petsalis-Diomidis, A. (2008) ‘The body in the landscape. Aristides’ corpus in light of The Sacred Tales‘, in: W.V. Harris and B. Holmes eds, Aelius Aristides between Greece, Rome, and the gods, Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition, vol. 33, Leiden: Brill, 131-150.

- Petsalis-Diomidis, A. (2010) Truly beyond wonders. Aelius Aristides and the cult of Asklepios, Oxford studies in culture and representation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Remus, H. (1996) ‘Voluntary association and networks. Aelius Aristides at the Asclepieion in Pergamum’, in: J.S. Kloppenborg and S.G. Wilson eds, Voluntary Associations in the Graeco-Roman World, London: Routledge, 46-175.

- Tozan, M. (2018) ‘Aelius Aristeides ve Galenos’un Eserlerinde Pergamon ve Çevresi / Pergamon and Its Surroundings in the Works of Aelius Aristeides and Galen’, in: N.E.A. Şahin, F. Onur and M.E. Yıldız eds, Eskicağ Yazıları 12, Akron: Eskiçağ Araştırmaları Kitap Dizisi 16, Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 133-176.

The Felsbarre

NW area with the Rock Spring

View from the Theater

View towards Pergamon

View from the SW corner

View from the Theater

The Roman bath

Rock Spring

View from the N Stoa

View from the W side of the sanctuary