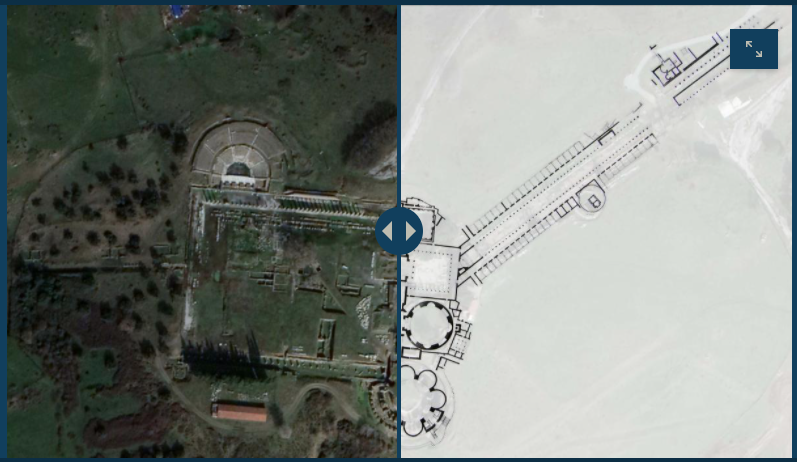

Good news! Since December of 2021 we are working together with the team from the Ancient History section of the Historisches Seminar at the University of Zürich. Under the direction of Prof. Dr. Andreas Victor Walser, and with Dr Ursula Kunnert, this team is tracking the inscriptions of Pergamon in the context of their project ‘Inschriften von Pergamon’. Their project aims to re-examine the inscriptions of Pergamon published by Max Fränkel in 1890 and 1895 (Alterümer von Pergamon VIII. 1-2), but also those from the Asklepieion that were published by Christian Habicht in 1969 (Alterümer von Pergamon VIII. 3). The project also compiles ‘new’ inscriptions that have only provisionally been published, or not yet at all. This exciting project will result in a new publication within the series Alterümer von Pergamon that promises to deliver many new insights that will surely lead us to rethink some of our interpretations of the Asklepieion as well as Pergamon in general.

Part of the project included a careful inventory of the current location of the inscriptions, and both Prof. Walser and Dr Kunnert have kindly and generously shared the results of many long hours in the sun and careful location and identification of the inscriptions, across the landscape of ancient Pergamon and modern Bergama.

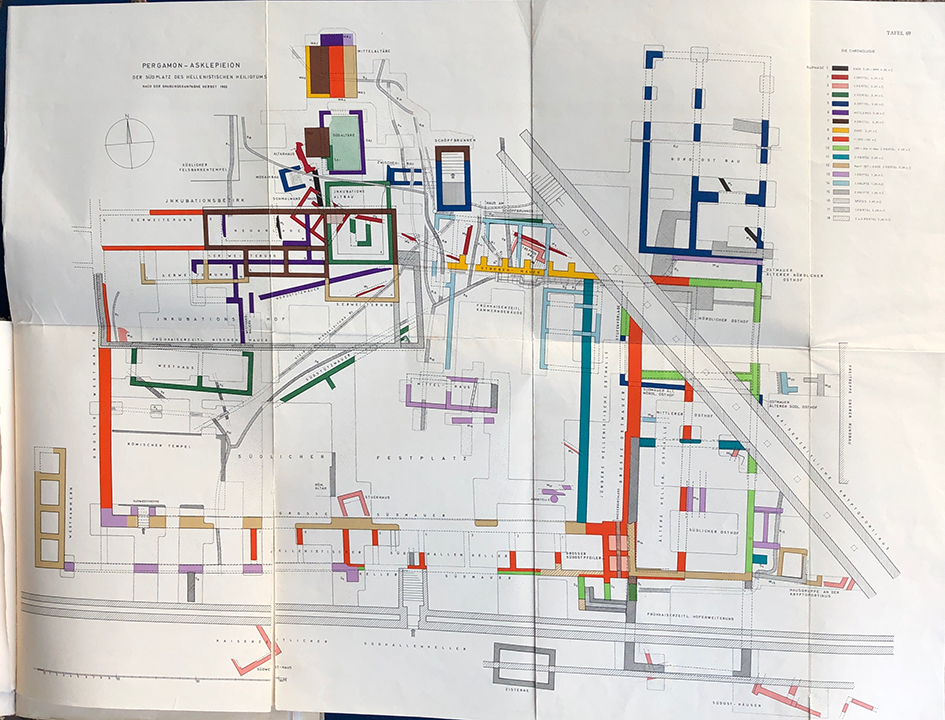

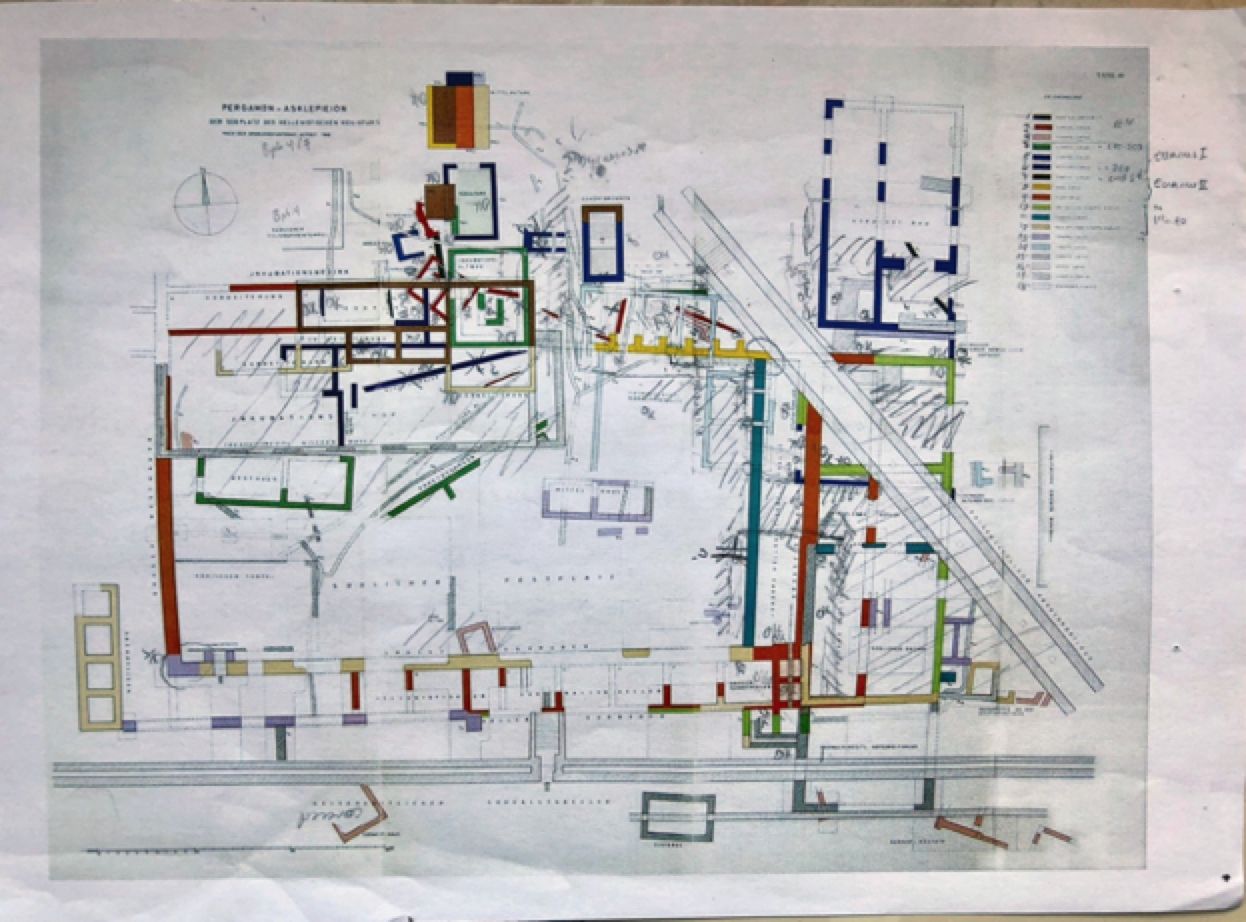

We are grateful to be able to include this level of detail in our deep map of the Asklepieion. This new modern layer of location has sparked some discussion on the mobility of monuments, both in ancient times, as some of extant inscriptions seem to have been moved to the North stoa of the imperial shrine, which seems to have functioned as a Hall of Fame, as well as in modern times, as some inscriptions are placed more or less near their original locations, others are kept farther away – some on site, some in the museum. We found ourselves asking who (across the ages) decides which inscriptions are seen, which are stored away?

These are important questions in considering the narrative function of a deep map!

Read more about the Zürich project here:

https://www.hist.uzh.ch/de/fachbereiche/altegeschichte/lehrstuehle/walser/forschung/pergamon.html